Authors: Kathryn Tyson, Liam Karr, and Peter Mills

Data Cutoff: June 7, 2023, at 10 a.m.

Key Takeaways:

Iraq and Syria. The Iraq and Syria section is on pause until the Salafi-Jihadi Movement Weekly Update, June 21, 2023.

Burkina Faso. Burkinabe forces greatly increased their operations against al Qaeda–linked militants near Burkina Faso’s southern border in May, which has likely temporarily degraded the militants’ support zones in the area. The uptick in operations is in response to the growing presence of the al Qaeda–linked group in the area throughout 2023. The al Qaeda–linked militants will likely maintain their support zones in southeastern Burkina Faso and strengthen them as Burkinabe forces scale back counterterrorism pressure over time, using nearby havens along the borders with Benin, Ghana, and Togo.

Pakistan. The Afghan Taliban may be aiding Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) efforts to coerce Pakistan into entering negotiations by supporting TTP attacks in Pakistan. The Taliban stated it will relocate TTP militants and other Pashtun refugees away from the border with Pakistan, likely to persuade Pakistan to negotiate with the TTP. The Taliban may be seeking to manage relations with the TTP and Pakistan. The Pakistani government has repeatedly asked that the Taliban address TTP safe havens in Afghanistan in recent months.

Afghanistan. Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) resumed conducting attacks after a two-month operational pause and assassinated a Taliban deputy governor in Badakhshan Province, northern Afghanistan. ISKP’s use of a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) indicates it has likely established a support zone around the provincial capital of Badakhshan Province. Taliban security measures have so far been insufficient to prevent ISKP from repeatedly assassinating local Taliban leadership in Badakhshan.

Assessments:

Burkina Faso. Burkinabe forces greatly increased their operations against al Qaeda–linked Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) near Burkina Faso’s southern border in May, which has likely temporarily degraded JNIM’s support zones in the area. Burkinabe security forces carried out 12 operations in Burkina Faso’s southeastern Centre-Est region in May, after averaging only one per month from January to April 2023.[1] This reflects the continuation of an upward trend in the security forces’ operations against JNIM since the last quarter of 2022, when they conducted only one operation.[2] The rate of JNIM attacks in Centre-Est decreased in late May after the increase in Burkinabe counterterrorism operations.

JNIM has not conducted an attack in the region since May 22.[3] Half of the Burkinabe operations in May were drone strikes, however.[4] CTP previously assessed that an overreliance on drone strikes will not lead to lasting counterterrorism gains.[5] Drone strikes are suitable for degrading JNIM’s support zones and ability to organize large-scale attacks. However, they do not address the inherent manpower shortage that inhibits Burkinabe forces from destroying JNIM’s capabilities or denying the group the ability to operate in the target areas.

The uptick in operations is in response to JNIM’s growing presence in the region. JNIM has averaged over four attacks per month in Centre-Est in 2023, which is more than double its average monthly rate in late 2022.[6] JNIM is trying to expand its support zones in this area by targeting civilians and degrading Burkinabe lines of communication along the roads connecting central Burkina Faso to the southern border.[7] Most Burkinabe operations in Centre-Est in May targeted JNIM forest bases that support JNIM’s activity.[8]

Figure 1. JNIM and Burkinabe Forces Contest Southeastern Burkina Faso

Source: Liam Karr.

JNIM will likely maintain its support zones in southern Burkina Faso and strengthen them as the Burkinabe security forces scale back counterterrorism pressure over time. JNIM has strong support zones in the neighboring Est region along the border with Benin and Togo that it can use to re-infiltrate Centre-Est if counterterrorism pressure subsides.[9] JNIM also has rear bases in northeastern Ghana it can use for similar purposes.[10] A large clash that killed dozens of Burkinabe soldiers and JNIM militants in one of the Centre-Est forest havens on June 5 further shows that JNIM maintains a significant presence despite the increase in counterterrorism pressure.[11]

Figure 2. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

Pakistan. The Afghan Taliban may be aiding TTP efforts to coerce Pakistan into entering negotiations by supporting joint TTP and Hafiz Gul Bahadur (HGB) group attacks in Pakistan.[12] The HGB group is a TTP affiliate with close ties to the Afghan Taliban and Taliban Interior Minister Siraj Haqqani. The HGB and TTP conducted two joint attacks in Bannu district in northwestern Pakistan on June 3.[13] The groups’ coordination in attacks represents a change in their relationship, as the HGB group has typically operated independently of the TTP.

The Taliban stated it will relocate TTP militants and other Pashtun refugees away from the border with Pakistan, likely to persuade Pakistan to negotiate with the TTP. The Taliban spokesperson said on June 5 that the Taliban would move thousands of “refugees” in eastern Khost and Kunar provinces to “far-flung” provinces in Afghanistan with the goal of preventing cross-border attacks in Pakistan. The link between “refugees” and cross-border attacks into Pakistan indicates the Taliban is referring to TTP militants because the TTP uses Afghanistan as a safe haven for such attacks. Pakistani officials have refused talks with the TTP unless the Afghan Taliban addresses TTP havens in Afghanistan. The Taliban also did not indicate when or where it will relocate the TTP militants and refugees.[14]

The Taliban may be seeking to manage relations with the TTP and Pakistan. The Pakistani government has repeatedly asked that the Taliban address TTP safe havens in Afghanistan in recent months. The Pakistani and Taliban foreign ministers struck an agreement on May 8 to combat terrorism and improve bilateral ties.[15] The Taliban and TTP are allies, and negotiations have benefited the TTP in the past by allowing the TTP time to rebuild forces and plan attacks.

The TTP is mitigating internal divisions over peace talks with Pakistan and may be rejecting “rumors” of talks to maintain internal cohesion. The TTP spokesperson denied that the TTP is seeking talks on June 7.[16] Some TTP factions do not want talks with Pakistan, and a prominent faction in the TTP condemned TTP leadership for a cease-fire with the Pakistani government in 2022.[17] Unspecified Pakistani officials claimed that the TTP had repeatedly proposed negotiations in June.[18]

Figure 3. TTP Attacks and Pakistani Operations Against the TTP

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

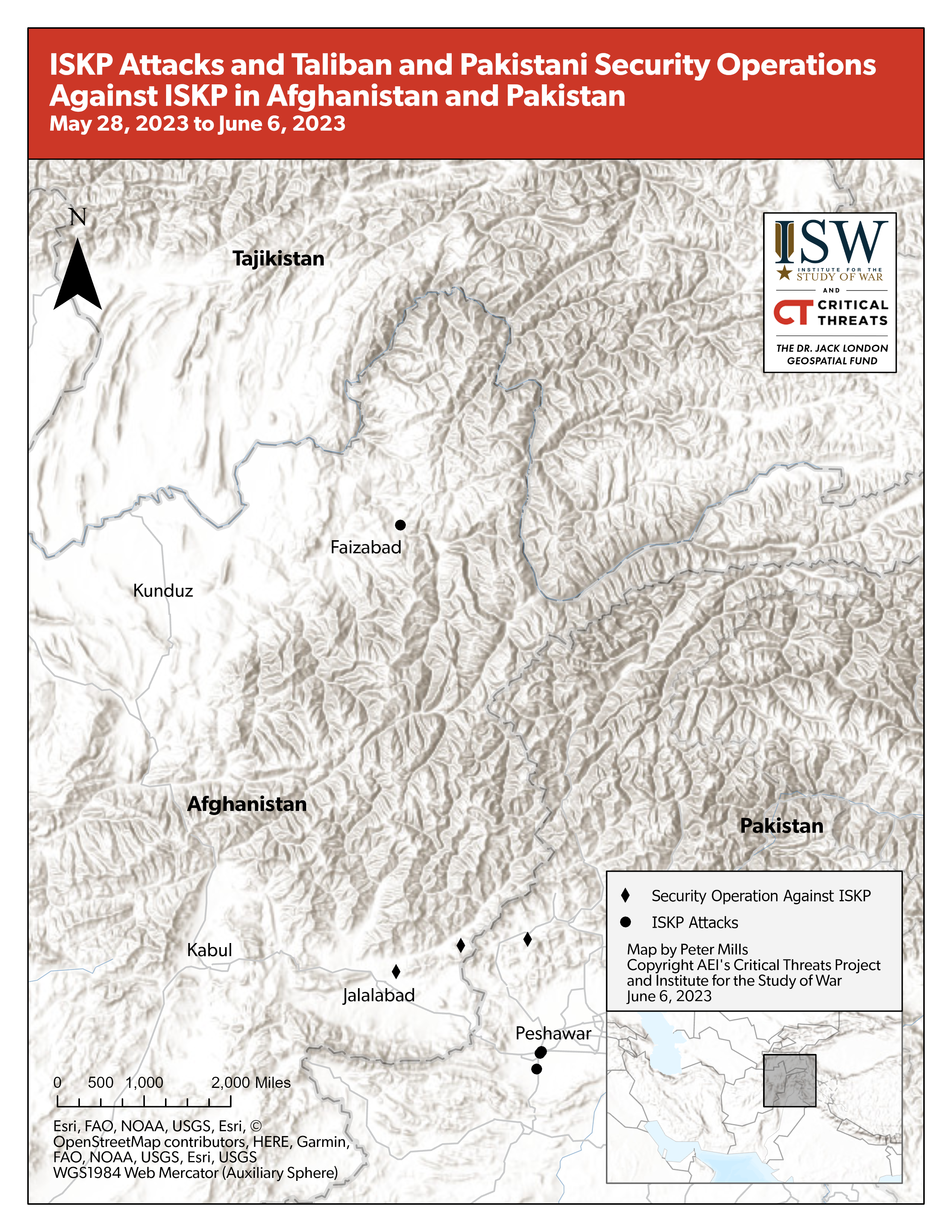

Figure 4. ISKP Attacks and Taliban and Pakistani Security Operations Against ISKP in Afghanistan and Pakistan

Source: Peter Mills.

Afghanistan. ISKP resumed attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan after a roughly two-month operational pause. ISKP detonated a VBIED and assassinated the Taliban deputy governor of Badakhshan Province in Faizabad, the provincial capital of Badakhshan, on June 6.[19] ISKP last claimed an attack in Afghanistan on March 27, when ISKP bombed the Taliban Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kabul.[20] ISKP also carried out three targeted assassinations of local government officials and Muslim religious leaders in Peshawar, Pakistan, since May 28.[21] ISKP last claimed an attack in Pakistan on April 13.[22] ISKP may have used its operational pause to recover from recent leadership losses due to Taliban counter-ISKP operations.

ISKP has likely established support zones in and around Faizabad, Badakhshan Province, despite Taliban counter-ISKP operations in northern Afghanistan. ISKP rarely uses VBIEDs because the weapons require greater logistical infrastructure to assemble and deploy than simpler improvised explosive devices. ISKP previously used a VBIED to assassinate the Taliban police chief for Badakhshan Province on December 26, 2022.[23] ISKP’s repeated use of VBIEDs to assassinate top Taliban leaders in Badakhshan indicates ISKP has the local logistical infrastructure to deploy VBIEDs in Faizabad. The Taliban’s counter-ISKP operations detained an ISKP propagandist in Badakhshan in February 2023, which indicates ISKP networks in the area are supporting ISKP information operations.[24]

ISKP’s attacks in Badakhshan also demonstrate that local Taliban security measures are insufficient to prevent ISKP assassinations of senior local Taliban leaders. The Taliban conducted more counter-ISKP operations in northern Afghanistan in March and early April than between January and early March of 2022. The increase in Taliban operations this year followed ISKP’s assassination of a senior Taliban leader, as CTP previously assessed.[25] Local divisions between the Taliban leadership in Badakhshan could also be undermining the Taliban’s counter-ISKP effort.[26]

Taliban Opium Ban. The Taliban is enforcing a ban on opium production, which could generate popular support for anti-Taliban groups if the ban is extended into 2024. The ban has reduced opium poppy cultivation by 99 percent across Helmand Province and more than 80 percent across all of Afghanistan.[27] Landholding elites in southern Afghanistan stand to benefit in the short term because they can sell their preexisting opium stocks at higher prices due to the ban. Their stocks will run out over the long term, however, so long as the Taliban continues to enforce the ban. Poorer Afghans who earn their wages through opium poppy cultivation will suffer as they lack their own stocks of opium.[28] Landholding elites and land-poor laborers who lose their primary source of income from opium could turn to supporting anti-Taliban groups.

The Taliban may not impose another opium ban for the fall 2023 poppy planting season. The Taliban has not previously sustained such a ban over multiple years and does not have an alternative to replace the income generated by opium farming. Afghanistan is mired in an economic crisis, which the Taliban is struggling to address.[29]

Figure 5. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Central and South Asia

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

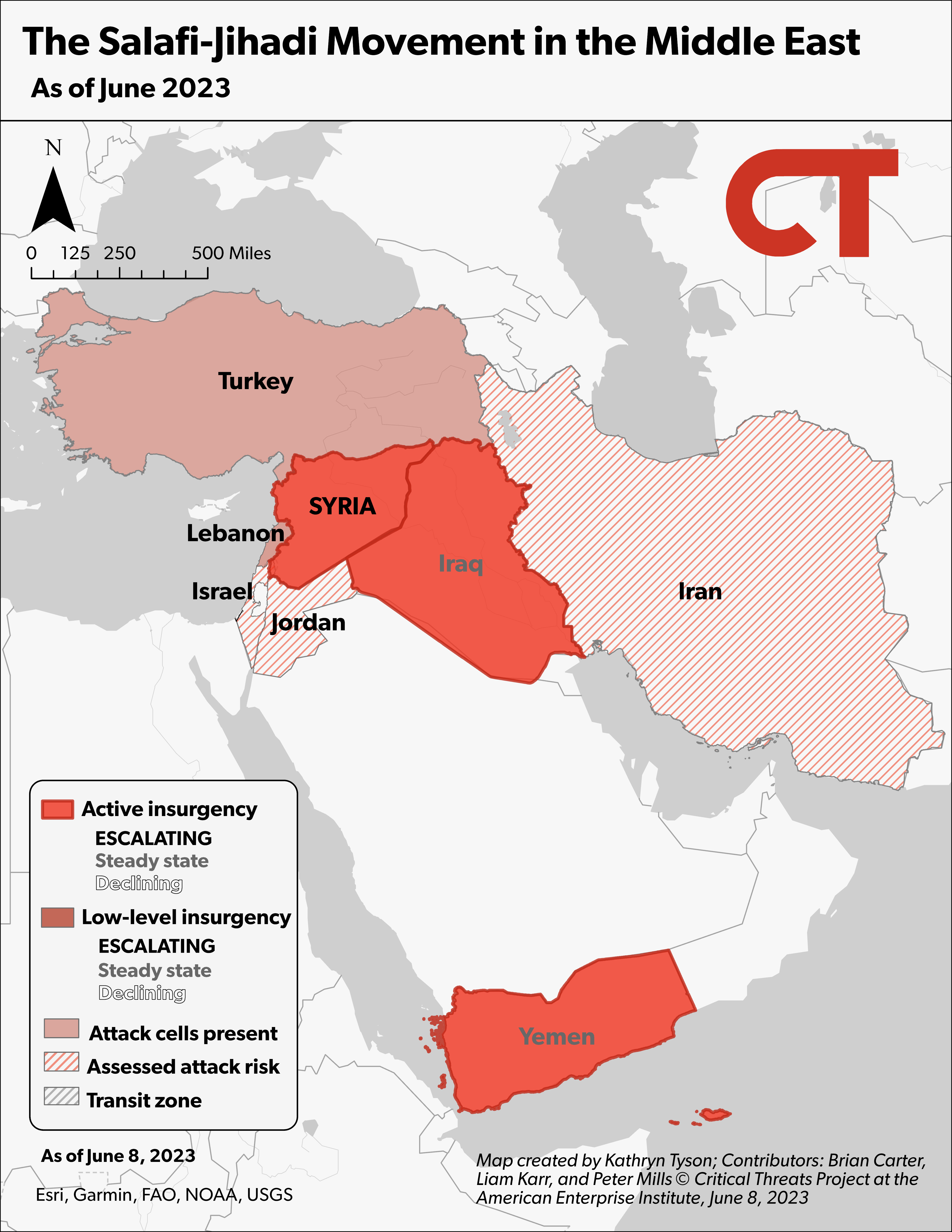

Figure 6. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Middle East

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

[1] Author’s research.

[2] Author’s research.

[4] Author’s research.

[5] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-5-2023#Burkina20230405

[6] Author’s research.

[7] Author’s research.

[8] https://www.aib dot media/2023/05/08/burkina-les-forces-combattantes-infligent-des-lourdes-pertes-aux-terroristes-dans-plusieurs-localites; https://twitter.com/Wamaps_news/status/1661366536378957833?s=20; https://twitter.com/Danoumis_Traore/status/1661466943533064193?s=20; https://twitter.com/Danoumis_Traore/status/1661466943533064193?s=20; https://www.aib dot media/2023/05/31/burkina-plusieurs-bases-terroristes-detruites-du-materiel-recupere-actualisee/?fbclid=IwAR3I5j3GGcUJ3uM19XHIbHJ3aaduXUPKCrJUPFFlTYIQZDnwNpK84Sbnwh0

[9] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-5-2023#Burkina20230405; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-february-22-2023

[10] https://twitter.com/EliasuAlhaji/status/1662379014567129088?s=20; https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Obs-Sahel_Note-10_version_web.pdf

[12] https://tribune dot com dot pk/story/2420442/pakistan-pours-cold-water-on-ttps-talks-offer

[13] https://twitter.com/cozyduke_apt29/status/1665319726279704576; https://twitter.com/cozyduke_apt29/status/1664857656333565952

[14] https://www.voanews.com/a/taliban-move-to-address-pakistan-s-cross-border-terror-complaints/7122978.html

[15] https://apnews.com/article/pakistan-afghan-taliban-trade-security-cooperation-aaf2b89a22164c42825e21d82e1cc98e

[18] https://tribune dot com dot pk/story/2420442/pakistan-pours-cold-water-on-ttps-talks-offer

[21] https://twitter.com/AfghanAnalyst2/status/1663088461606187011; https://twitter.com/ShabbirTuri/status/1665004043230478344; https://twitter.com/AfghanAnalyst2/status/1664493186570493953

[23] https://www.afghanwitness.org/reports/badakhshan-police-chief-killed-in-a-vbied-attack-in-fayzabad

[25] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/salafi-jihadi-movement-weekly-update-april-5-2023